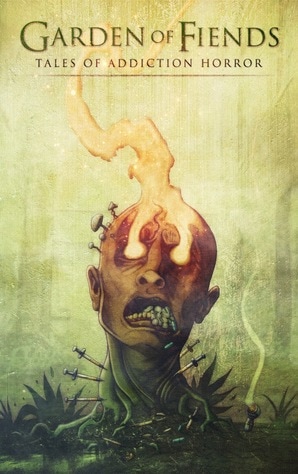

There's often a sincere degree of fear when I come across any media that purports to explore subjects as complex and volatile as addiction, substance abuse etc. The tendency for writers and artists to regard those subjects as merely resources to be mined; potential fodder for creation, is as well testified to in popular work as is the proclivity for said work to profoundly misapprehend their minutiae and ambiguities. That factor is amplified to the power of N when said work comes couched under the label of horror, which, despite being a genre that I adore more sincerely than any other, has a tendency to simplify such matters in moral terms and human significance. It is a rare, rare thing indeed for collections of short stories cohered by the subject to explore anything close to the genuine, human experience of addiction; the sensory and psychological elements, the wider ramifications and impact. Such tend to be thinly veiled political or socio-cultural screeds designed to inflict some “point” on the reader, to bend their perceptions or biases this way or that, regardless of the writer's own experience and/or considerations. Taking into consideration the title, one might be forgiven for initially assuming that Garden of Fiends is exactly that; a set of moralistic and finger-wagging fables designed to warn the reader of the perils of substance abuse (of an ilk that are, to my mind, inevitably self-defeating; ignorant of the innate perversity of human nature, despite our most historically enshrined mythologies making such overt in their opening chapters). It is therefore a sincere pleasure -not to mention relief-, to report that Garden of Fiends is anything but; a collection generally not intended to demonsie the addicted or even addiction itself; not restricted by any particular moral dogma or political screed. Rather, its stories attempt to explore what addiction and substance abuse are in distinctly human terms: almost every tale in the collection is from the perspective of characters with persistent and increasingly aggressive monkeys on their backs, from alcoholics to heroin addicts, from habitual gamblers to those afflicted with more abstruse and abstract appetites, the collection is interested in exploring what addiction is and what it means in human -rather than political or socio-cultural- terms, which makes it immediately more appealing than a thousand others that have purported to plumb the subject, but are only interested in sermonising. Whilst not an addict per se myself (at least, not in any way that culture at large would consider debilitatingly so, unless coffee and chocolate count), I sincerely appreciate that the stories in this collection are not interested in making me snarl and beat my chest in tribal affirmation or moral condemnation; from the opening piece on (a first-person account of one man's alcoholism and the genuine disgraces it drives him to), the collection wants the reader to see its characters as people first and “addicts” second. Whilst addiction is clearly the principle factor at play in their lives, it is not all that defines them; they are complex and ambiguous, sympathetic and infuriating, by turns hateful, by turns heart-wrenching in their manifold tragedies. These are people who are as much victims of circumstance as they are monsters of their own making; the element of choice involved in any addiction weighed against the situations and circumstances that cultivate and fuel it becomes a central tension, one that is presented in fittingly ambiguous and none-didactic terms. Those seeking a tract to fit whatever dogma or agenda they personally cleave to would do better looking elsewhere, as this collection is unconcerned with the inevitable synthesis that occurs under such restrictions. Unlike so many of its peers, it involves both writers and collators who have first-hand experience of addiction, and therefore have an eye for the details that ring true and those that are simply ornamentation or window-dressing. As such, the stories have a degree of immediacy and impressionistic quality that is all too rare in many, and lends each account a human quality beyond any that are contrived from thin air or in the interests of emphasising some ideological point. One might be forgiven for declaring addiction and substance abuse unfit subjects for horror fiction, given the genre's tendency to exaggerate, distort or simplify for the sake of eliciting visceral response. Garden of Fiends is one of the few that shirks such tendencies and has the wherewithall to explore addiction in every particular, no matter now unpalatable those factors might be. There are no safe spaces or blind eyes, here; the stories relay the most sincere of human disgraces, degenerations and ultimate tragedies, but also have no qualms concerning what dark joy addiction can be, in terms of its satisfaction, the dreaming distance it so often provides from consequence and waking reality. In that, the collection is notable in its appreciation of ambiguity; of highly politicised material that is far, far more complex than any proscribed perspectives or commentaries thereon allow for. The collection might prove alienating for those who seek something lighter or less acutely resonant in their horror fiction; this is not material that seeks to divert or distract from the more unpleasant or unpalatable aspects of human experience, but to explore it often in the most vivid and repulsive detail; these are tales of human disgrace; of how deeply we fall when the abyss of appetite yawns beneath us. Almost every story involves explicit scenes of human beings engaging in the most self-denigrating and atrocious behaviours in order to satisfy imperatives that overwhelm all else, from an alcoholic who commits unconscious murder whilst in the throes of a deprived and tortuous sleep to one who readily slices and sells away portions of his own flesh for just a sniff of chemical bliss, the stories elicit as much repulsion as they do degrees of sympathy; a juxtaposition that many may find somewhat difficult to take, especially given the depths that some characters plumb. In that, Garden of Fiends has a consistent, over-arching theme; every story concerns men and women who assume themselves lost, but who have much, much further to fall than even their initial states of disgrace suggest: without exception, they all end up becoming so much less than they begin, or rather, realising the ultimate states of disgrace that their addictions inevitably manifest: the collection is unshirking in that regard without becoming finger-wagging or overly moral; it simply concerns itself with the personal realities and wider social fallout of addiction, even in circumstances when the stories involve subjects that are more outre or fantastical. This is an experiential rather than moral or even socio-political leaning collection; the commentary it provides is not didactic or finger-wagging; rather, the stories provide descriptions of a more visceral kind; of the depths and extremities that addiction of various kinds drives people to, both in terms of what they are willing to do -to others and themselves- and what they are capable of enduring (the states of squalor, destitution and disgrace painted here are pungent; the writers generally make a point of ensuring that the reader can feel and smell and taste what their characters experience; a factor that some might find off-putting, if not entirely repulsive). Whilst some readers (myself included) may be attracted to the vicarious sensory experiences and states of disgrace the collection offers, many may find their detail and candidness too much; this is not a collection that shies away from the more morbid, grotesque or denigrating aspects of addiction, rather, it grasps the reader by the head and presses its face into the filth. It wants you to experience what the characters are experiencing; to know their pain, their want, their humiliation, but most of all, it wants you to see how swiftly states of disgrace become normalised; how addiction distorts perception to such a degree, that its victims quickly come to accept conditions that they wouldn't even consider in states of sobriety. Here, you will find stories of men and women mutilating themselves in the most graphic and intimate ways simply for a moment's bliss, stories of those who are willing to sacrifice and abandon everything in the name of their chemical needs. The mental images drawn are often (deliberately) grotesque and repellent, but more so is the almost casual manner in which their subjects come to be part of them; those who no longer have any recourse for satisfying their urges and appetites surrendering all that they have and more for what seems almost nothing, from an external perspective. Perhaps more distressing than any of this are the worlds in which these stories operate, most of which are not a million miles away from those that their readers inhabit, but often cultivate and proscribe the conditions in which addiction runs rampant or where its victims inevitably fall prey to themselves and one another. Though any socio-cultural or political commentary is generally suggestive or implied, such resonates throughout the entire collection as a kind of background beat or cohering rhythm, deriving largely from ambient details of the uncaring or entirely hostile worlds in which the variously addicted characters operate: for most, it is the case that cultural circumstance has led them to their states of addiction and allows for the factors that see it escalate to eventual self destruction. In others, it is suggested that the states and cultures of addiction are actively sustained or mandated, as a means of maintaining particular political and/or commercial status quos; vested and extremely powerful interests thriving in the conditions of human misery and desperation they foment. In that, the layers of horror one might experience from reading the collection vary; from the more intensely personal and human reactions that derive from the states and situations characters find themselves in to a more profound, resonant despair at the powers and institutions that parasitically swell upon that cancerous status quo, the significance of the collection depends largely on what the reader brings to it and what they are willing to take away. Again, this degree of commentary may prove alienating for those who wish their horror to be lighter and more whimsical; less concerned with confrontation than with escapism and vicarious thrills. But for those who seek something a little deeper, a little darker; perhaps somewhat more personal and even “triggering,” then this collection will likely satisfy that itch; an appetite and addiction that itself is too often denied in mainstream markets. Title: Garden of Fiends Publisher: Wicked Run Press Edited and Collated by: Mark Matthews Purchase Garden of Fiends here:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorGeorge Lea is an entity that seems to simultaneously exist and not exist at various points and states in time and reality, mostly where there are vast quantities of cake to be had. He has a lot of books. And a cat named Rufus. What she makes of all this is anyone's guess. Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed