Well, spatter me in raw, red and wet surprise. Who in their right minds would have thought this would work? Adaptations of video game franchises to screen -or any other format- have a nasty tendency to disappoint at best; usually either too far from the source material to warrant sharing its name or so slavish they murder themselves in the effort to recreate it verbatim. The announcement of Netflix's adaptation of Konami's classic Castlevania franchise into an animated TV series certainly intrigued initially, if only for its strangeness and near absurdity: whilst the franchise continues to this day in various different forms, most recognise it as a 2D, side-scrolling platformer with a gothic horror bent, from a time when stories in video games could be consigned to half a page in instruction booklets. Whilst Castlevania certainly has a number of rich seams of mythology to draw on, cohering them into something recognisable as the video game and not just another weary vampire anime was always going to be a daunting task.  More than anything, curiosity is what made me sit down to watch the first instalment. They got it right. Very, very right indeed; not in the sense that the series serves as a recreation of the video games, rather that the creators have somehow struck that fine balance between paying enough homage to them as to be recognisably part of their universe, whilst simultaneously elaborating upon that universe sufficiently to make the show its own entity. Opening on the eponymous structure itself, eminently recognisable to anyone who's played any of the games as the architecturally impossible, non-euclidian castle that is Dracula's lair; an insanely elaborate edifice far, far removed from classic depictions that dominate written fiction and cinema, the show immediately impresses with its design and atmosphere. A stunningly rendered, foreboding structure, insane in its gothicism, looking as though parts of it float without anchor to the rest, others resembling the interiors of warped clocks or shattered sea shells, it's an arresting image, and one that pervades the entire show. Dracula himself is also a surprise; threatening, malevolent, but also patient, charming and sympathetic, at least initially; a take on the character that neither the games nor the fiction from which they derive provide, closer to the love-lorn monster of Francis Ford Copolla's 1992 adaptation than the unambiguous hellspawn of the original novel. Quiet, poised, charming; a monster, certainly but one not without thought or conscience. This incarnation of the classic myth establishes that, whilst there are certain synchronicities with those that have gone before, both the iconic vampire and the world in which he occurs are removed from what most would recognise: this is not, for example, the familiar Transylvania of the original novel and the majority of its film adaptations; rather, this Dracula occurs in the semi-fictional Wallachia; a pseudo-European nation, seemingly composed of various smaller territories all of which are named after places that fans of both classic Dracula lore and the video game series will recognise. Likewise, it doesn't appear to be set in any particular time period; Dracula's castle itself, as in the video games, simultaneously gothic and science fiction in composition, its interior boasting as much in the way of technology as it does gargoyles, sepulchres, tapestries etc. Whilst the series doesn't delve too deep into Dracula's background, there's certainly an abiding suggestion that he is a timeless, immortal entity whose scope and intelligence transcend humanity's so as to render him alien to them. Dracula actively removes himself from previous incarnations of the character by describing the nature of his castle; apparently an “engine” that can move through time and space at his will.  The first few scenes also establish how strongly characterised even the supporting or incidental cast are; whereas in most incarnations of the myth, the woman who will eventually become Lisa Tepes, Dracula's wife, would have been a victim to establish Dracula's heinousness and monstrosity, here, she's a head-strong, intelligent and wilful woman who not only survives her initial meeting with the vampiric count but charms him with her humanity; a woman of reason and science who seeks to break the stranglehold of superstition and religiously proscribed ignorance that blights Wallachia. The series, wasting no time, given its limited run, fast forwards some years from this point, to the ritualistic burning of Lisa at the church's behest for the “crime” of witchcraft. Economy of storytelling and establishment of character is all important here, as the show is extremely short, given the density of back mythology and range of characters it attempts to convey, and it does so with remarkable impact, Lisa herself barely on screen for more than ten minutes, from the moment of her introduction to the point of her death, but becoming the fulcrum upon which the entire show turns: her death serves to establish the hideous corruption of the church that dominates Wallachia, the lust for power that pervades its upper echelons, but also the factor that drives Dracula -who has been “wandering as a man” at his wife's behest- so deep into grief and misanthropy that he unleashes all Hell upon humanity.  Fans of the game might find this curious for an opening episode, as, although we do meet franchise favourite characters such as Alucard, Dracula and Lisa's son, there's not a sigh or suggestion of the Belmonts, who tradtionally have been the player characters in most Castlevania games, until episode 2. That said, the show utilises what chance it has to establish the rules and dynamics of its universe beautifully, very little stated outright; much left to implication and visual cues, raw atmosphere and emotion the core of its appeal, the dynamics between the characters natural, immediate and complex, the powers at work within its world established without redundancy. As for protagonist Trevor Belmont, his characterisation may come as something of a surprise to fans of the franchise; far from the dauntless hero of the video games, Trevor is outcast and disgraced, the Belmonts themselves a family whose excommunication by the church has driven them to dereliction. We first find Trevor drunk and near pennilless in a village bar, begging for drinks, stinking to high Heaven, getting into bar fights with the locals, where he demonstrates something of the capacities that made his family celebrated monster hunters, but not enough to keep him from disgrace. Like many of the characters in this series, he's ambiguous at best; a sardonic, vagrant man who seems to only care about where the next drink is coming from, drawn into the conflicts between Dracula's hordes and the church by circumstance and accident, though glimmers of the man he might be do start to show through the accrual of disgrace. Funny, eloquent and bitter, Trevor is a surprising take on a character who could have been easily two dimensional and dully heroic, forced into defending people he doesn't particularly like, and who are so sheepish in their desperation and blind faith they almost end up murdering him at the church's behest at various intervals.  Regarding the church, some veiwers might be alienated by the show's portrayal of religion: there is no subtlety or nuance, here: the church -which, whilst not specifically named as the Catholic church, is this world's equivalent thereof in almost every respect- is an unambiguous force for harm in this world; not only is it the self-serving misogyny and cruelty of the church that brings Dracula's wrath upon the land, but it is the church that seeks to capitalise on the situation to secure its powerbase, turning the people against whatever scapegoats prove convenient so as to further secure their authority, which, inevitably, brings them into conflict with Trevor Belmont and his allies. Interestingly, the vein of misanthropy that runs throughout also lends the show a certain moral ambiguity; whilst Trevor and those who eventually fall in line with him are portrayed as the heroes of the piece, the weakness, sheep-like naivety and scapegoating tribalism of most of the people they encounter, not to mention the manifold atrocities committed by the church, has the effect of making the viewer -at least in my case- side almost entirely with Dracula. As Dracula himself points out, the species demonstrates again and again that it is worthy of no better; he is merely wiping the slate clean, hastening the demise and damnation it will inevitably bring upon itself. The show is also surprisingly true to its horror roots, despite being based on a franchise that made its name when video gaming in the West was aimed squarely at younger demographics; full to brimming with blood, gore and dismembered body parts; images of demons tearing apart men, women and children, devouring babes...the Hell that Dracula unleashes is quite literal; elemental evil made manifest in the world, and therefore all of the very worst he can visit upon humanity is rendered here, without conscience or ambiguity. Do not think that, like many shows of its ilk, children or women or the elderly are somehow involate; there are no innocents, as Dracula himself proclaims, in the depths of his grief, and so, the show provides none: only deeper and deeper atrocities, escalating situations of pain and grief and despair.

It's an interesting note to go forward on, these four episodes largely serving as an extended pilot episode to establish the back mythology, principle players and dynamics of the story. In that, it leaves the viewer somwhat unsatisfied, as it feels as though it ends just as the action picks up pace, but this is entirely intentional, ensuring that a significant number will be clamouring for when the show hauls itself from the circles of Hell once more and wreaks havoc on the living. Short, violent, surprisingly sophisticated, grimly charming; arguably a candidate for the most successful video-game-to-screen adaptation ever attempted.

0 Comments

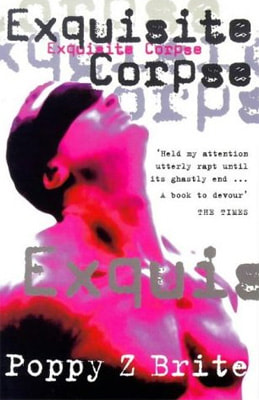

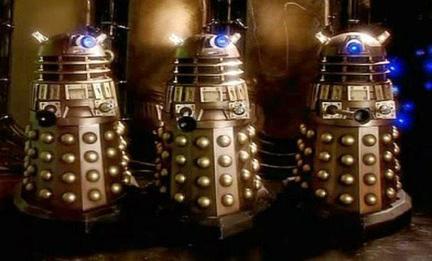

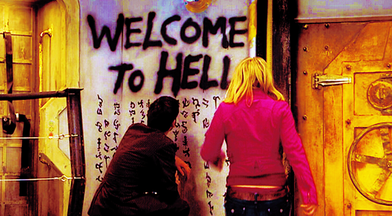

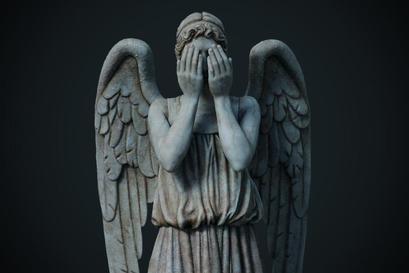

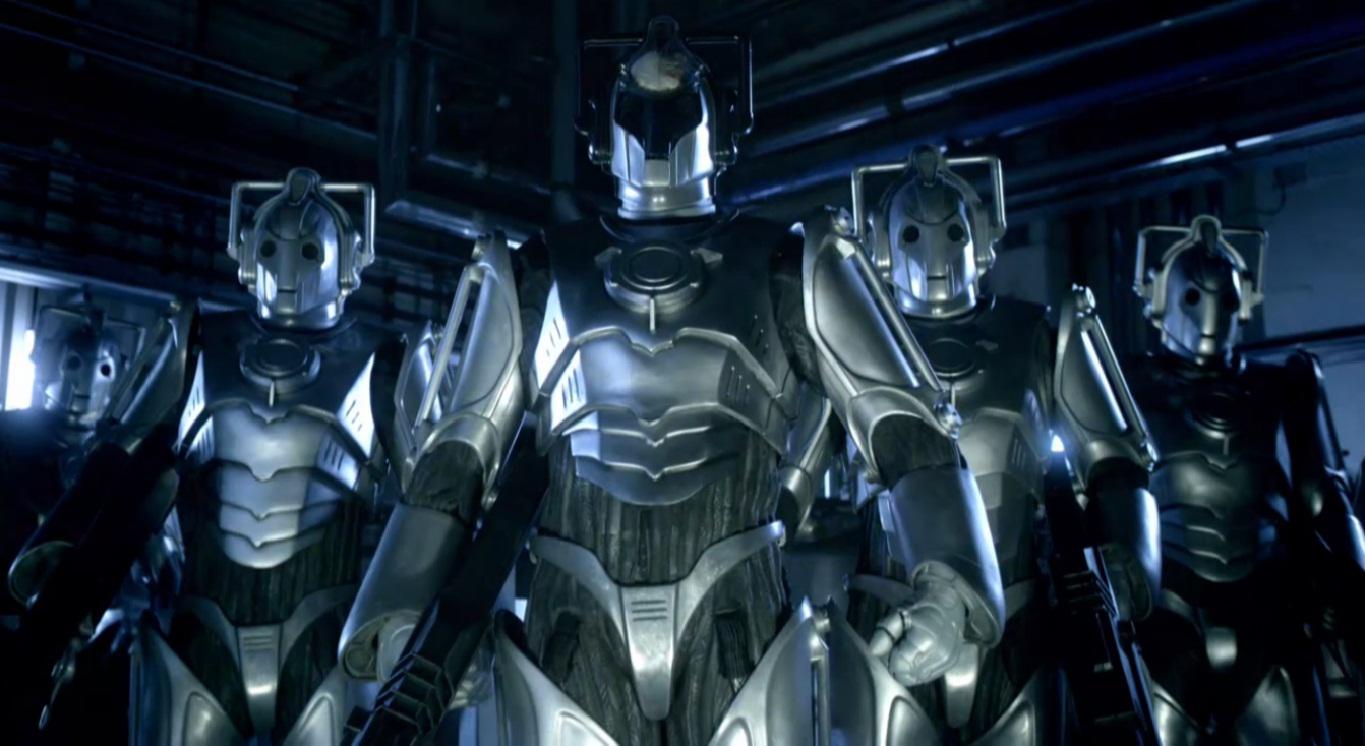

Returning to something once loved after a long absence...often not the most positive of experiences. Be it a film, a book, a work of art; a lover, there's a tendency for change to alter perception but also what one demands and desires from those experiences, rendering any attempt to recreate old states of mind and emotion redundant; self-corrosive by nature. Exquisite Corpse was one of many, many works through which I survived my late teens and early -to-mid twenties. Without its like, I wouldn't be here now; social anxiety, insomnia, depression...one or all would have claimed me, existing inside my own skull becoming too tortuous to bear. In their darkness, their frequent nihilism, misanthropy; their passion and poetry and characters as lost and confused and unhappy as I was, I found some avenue of expression, a way of articulating to myself what was wrong, but also what I might take joy in, if I only had the urgency of appetite to step outside of myself and find it. Exquisite Corpse was one of many read and re-read again obsessively, on buses to and from university, at night in bed, in cafes and bars whilst lectures I probably should have attended passed me by. I fell in love with its characters in ways I found impossible with most in my waking life; characters my affection for I still find strange and disturbing; universally broken, ambiguous, powerfully amoral people, from casual drug dealers to murderously jealous lovers, from caring but unconsciously bigoted parents to cannibal, necrophile serial killers...all presented as equal parts of the stew of humanity, the book notably amoral in terms of its framing and lack of judgement; it neither loves nor hates its characters, demonstrating profound affection for them all, in its own peculiar way, revelling in memories of lost love and sexual pleasure as much as it does the visceral, sadistic joy of a serial killer's eviscerations, a necrophage's repastes. That factor was a revelation for me; that fiction does not need to heap judgement on its characters; to sermonise its readers, but can take unambiguous joy in their company, no matter how ostensibly loathsome, how morally absent their behaviours might be. The joyous wantoness of it, the abandon it revels in, combined with a sweet sincerity, mercifully bereft of sentiment...characters who are beautiful and loathsome and attractive and repulsive by intervals and all at the same time. It's a shuddering and orgasmic sensation, to realise that you are attracted to characters who, in waking life, would perhaps inspire intrigue through their extremity, but also repulsion in terms of their appetites and behaviour. Serial killers, cannibals, necrophiles; drug-addicts and adulterers, all dimensions of human experience are explored here, in terms of not only the most explicit acts but also emotion; the book cultivates a sincere obsession with extreme states and conditions, placing its reader both in the position of sadist and victim; of murderer and murdered, treating no one with more or less affection than the other. As a timid, withdrawn, socially anxious gay boy in a barely-man's skin, Exquisite Corpse gave vent and expression to drives and inclinations I did not know existed; allowing me to walk in the skins of entities who are reptilian in their confidence, who are shimmering and beautiful in their strangeness, but also things of grotesque appetite and morbid obsession; who express their adoration of other human beings (and make no mistake; these characters are profoundly and explicitly human, no matter what metaphors you might draw to describe their states of mind) via mutilations; with knives and scalpels, with saws and hooks and chains and teeth. The kindred-souled killers of this book -Andrew Compton and Jay Byrne, both of whom act as composites of various “real life” serial killers, including Dennis Nilsen and Jeffrey Dahmer, respectively- are explored in the most intimate detail from the first instance; as human beings first and foremost, as “serial killers” not even second or third; whilst those appetites dominate and define to certain degrees, they are also complete and coherent characters in their own rights, from Compton's faintly prissy British sensibilities; his refinement and artistry, to Byrne's explosive penchant for grotesque theatrics, the far more overt sculptures and works of art he carves from his victims. Both exhibit a common characteristic of intense and unambiguous love for those they butcher; a desire to consume and control that they can express in no other fashion. As such, the scenes of murder and butchery are intermingled with the agonisingly erotic, the two co-mingling until they are difficult to discern. The reader is invited into their worlds, to feel as they feel, to hunger as they hunger, to love as they love; an invitation at least as seductive as any vampire or incubus might offer, albeit shorn of those entity's mythological trappings. The urge to be with such characters, even knowing with a reader's divine eye who and what they are, what they would do if they got their hands on you, is a strangely enticing and shuddering realisation; arousing parts of the reader's self that they may not have acknowledged before. Nor are the less extreme characters any less charming; from lost and lissome Tran, a Vietnamese teen only just feeling his way through his own appetites and inclinations, to embittered and broken Lucas Ransom, the man responsible for Tran's awakening, his former lover, now abandoned, shattered by the loss, slowly succumbing to recently diagonsed HIV...all are genuinely wonderful to be around, in all of their ambiguity, amorality; their contradictions and esctasies and despairs...barring Tran, who is as close to innocent as anyone or anything in this book gets, all are men who destroy what they love; who cannot help but be corrosive; Lucas with his barely concealed anger at the world, his general misanthropy, that, as Tran himself asserts, was in full swing long before their break up and the diagonosis that spurred it, Byrne and Compton through the expressions that love drives them to. Whilst Lucas could be said to be somewhat more stable than these two, there is some genuine overlap in terms of the way they perceive the world and humanity, that allows him to realise them for what they are, whereas Tran remains blithely and wilfully ignorant. Their interactions; the coincidences and circumstances that string them together, drawing them into one another's lives...the bloody theatrics that result...all heart-achingly compelling, all described from a deeply sensual, fleshy perspective that renders every setting and experience as a sensory painting; lurid, lingering strokes of scent and taste and texture scar every page, allowing the reader to smell and taste as the characters do; to share in their love making, sickness and atrocity in a manner that is beguiling, emotionally exhausting, but addictive; the book is a poorly healed wound, picked at and picked at, coaxed to bleed again and again, until any hope of healing becomes absurd. Returning to it in recent weeks, after so long an absence; after transformations and changes, the anxious, affrighted youth who first discovered it long since slaughtered, cooled, picked clean by whatever scavengers had a mind on his meat...a little like meeting an old lover, old betrayals stirring, as well as old pleasures. A delirious reunion, finding far more to appreciate in it, now that it is no longer necessary; that anxiety and depression and divorcement from my fellow queers no longer makes their company in fiction essential to sanity: something to revel in, in every bleak, nihilistic, sensual particular, where even the most hideous and discomfitting of sensations become toothsome, where the most monstrous in humanity is celebrated. As intense and passionate an affair as I remember, but one that operates on new and deeper dimensions, now that we're both older, and have learned a little of the world and one another. Make no mistake, Exquisite Corpse knows its audience; it speaks to a very specific sub-set of readers whilst deliberately alienating -and outright insulting- others; many will find its universal sensualism, its celebration of the most intimate morbidity, alienating, if not entirely atrocious; others will find the close focus on LGBTQ characters far outside their realms of experience, and therefore somewhat foreign or frictionless. For those the book casts its “come-to-bed” eyes at from the shadows, very little will sing as bitter-sweetly, or prove quite so generous in its affections. Exquisite Corpse can be purchased here.  I was born in 1984, so only knew of Doctor Who somewhat vaguely (much deriving from my Mother, who's been a big fan since the original show first aired). At the time of Russel T. Davies's resurrection (regeneration?) of the franchise, I had just started university; an extremely green-around-the-gills 21 year old with rampant insomnia, social anxiety and at the outer-edge of a bout of depression that had lasted almost a decade. I remember tuning in with sincere scepticism, my tastes in science fiction running more to the likes of Phillip K. Dick's existential paranoia and William Gibson's cyber-punk fare than the somewhat more fantastical, light hearted subjects I associated with the Timelord's adventures. The first episode I tuned in for was entitled Dalek, that marked the return of the Doctor's most iconic antagonists. Much of my intention for doing so was, admittedly, perverse; the promotional material made this episode look like the stuff of nightmares, yet I couldn't comprehend how something so patently ludicrous as the Daleks, with their pepper-pot forms, egg-whisk lasers and sink-plunger appendages, could ever be threatening. Needless to say, the episode made it a point of demonstrating just that: most Doctor Who episodes have some sort of body count; it is, after all, the nature of the franchise to include some sort of murderous alien or psychotic cyborg. The episode contains only one Dalek; a lost and damaged thing, initially barely alive. By the end of the episode, it has murdered the equivalent of a small settlement; trained soldiers, security staff, scientific personel and technicians...the episode does everything in its power to demonstrate how the Dalek's superficial absurdity and lack of elegance has no bearing on its capacity to, well, EXTERMINATE, which it does with surprising alacrity.  More than that, the episode expands on the Dalek's mythology as well as its immediate threat; we learn of its past relationship to the Doctor, see his spittle-flecked, tribal hatred for the species, come to understand that the Daleks once presented a threat to all of time and space. It's a fantastic example of how something intrinsically ridiculous can be leant degrees of threat and horror by its framing and presentation. This is before we get a glimpse inside of the “pepper pot,” and get to see the Giger-esque nightmare of the Dalek's interior form (a sort of octopoidal brain creature with a single, madly glaring eye).  Needless to say, by the end of the episode, I was hooked, and hungry to explore more of the “Whoniverse.” As already mentioned, almost every episode of Doctor Who has an element of horror involved; the central tension is usually established around an opening scene in which some uncanny threat is presented; a victim running afoul of some alien, robot, ghost or malfunctioning system. Some episodes are more explicit in this regard; following Russel T. Davies's initial series, it became part and parcel for there to be at least one “horror” episode per season, which ramped up the sense of dread and tension, paying homage to the genre's tropes and traditions. Being produced by a variety of writers, directors etc, the quality of these episodes and the nature of the horror they reference obviously varies, meaning that it's a rare instance in which any one episode appeals to all tastes and sensibilities, but it is notable that the vast majority of the “horror” episodes (from The Empty Child to Dalek, from The Impossible Planet and The Satan Pit to Don't Blink) consistently appear on “top ten” and “must watch” lists. The strongest of these episodes are those that not only pay homage to some form of horror trope or tradition, but attempt to transcend it; stories that acknowledge the bounds and parameters of those sub-genres (be they gothic, surreal, science fiction) and breaches or lampoons them to certain degrees. Doctor Who is a perfect vehicle for such genre-defying experiments, since it potentially contains any and all stories that might ever be told (the Doctor and his companions not only regularly travel through time, but -surprisingly often- end up in parallel worlds or universes or end up destroying and re-setting reality altogether, meaning that possibilities are endless). Not only that, but, being the hodge-podge of influences that it already is, adding in extra layers and depths of flavour doesn't poison the stew as it might for some, but generally allows the show to flex its muscles and demonstrate how complex it can potentially be. The fact that the show is bounded by its intended audience and airing time generally doesn't do much to hamper its horrific elements; though you'd never find grindhouse or gorenography levels of grue here, it generally doesn't shy away from moments of incredible pain, torment or mutilation; it merely delivers them in a more subtle, implied manner (for instance, the classic antagonists known as Cybermen are created by removing a human being's brain and nervous system from their body via -often involuntary- surgery, then transplanting them into a cybernetic exo-skeleton. The procedure, whilst not graphically detailed, is explained with somewhat gruesome relish by the Doctor, and is often implied via extremely unpleasant suites of sounds and fragmentary glimpses of the horror unfolding). That a show which airs on prime-time BBC even contains such elements is something to be grateful for; at its very best, the show serves to expose audiences of various ages and generations to material that they might otherwise be insulated from; not only emotions and sensations, but concepts and images specifically designed to lodge in developing imaginations and inspire as well as horrify, just as the show's original incarnations clearly did (writer Neil Gaiman, now a semi-regular contributor to the show, is verbose about his enthusiasm and the effect it has had on his world-renowned writings). What Doctor Who in terms of horror -at its very best, mind; a promise that it doesn't always fulfil- is a massive, mainstream platform for experimentation and exposure: the horror must necessarily be clever and witty and subtly conveyed in order to work and be acceptable to the vast range of eyes it reaches on a semi-regular basis (not so regular in recent years, sad to say). It has the potential to truly unsettle, disturb and inspire, as all the very best horror material does. That it doesn't always or even regularly is a massive disappointement and somewhat despair-inducing, as those of us who keep up with the show have seen it at its best, and crave more. It tends to diminish itself through a sense of complacency; when the writing becomes overly indulgent and self-referential, when it feels too secure in its status and position. The truly deviant and inventive stuff tends to come about in climates where it isn't certain of itself; when it's finding its feet and therefore wide open to experimentation and a degree of external influence. As with all such franchises, it's when it becomes closed off; hermetically sealed and protected (largely as a result of success and a great deal of money being made) that creativity and deviance start to wither; when we start to see certain tropes and concepts being repeated ad nauseum (try to count the number of episodes in which a seemingly supernatural phenomena turns out to be the result of some failing technological system. I dare you). This is when any semblance of horror necessarily dies, as it's impossible to distress or disturb the audience with stories whose every turn they can predict through sheer familiarity.  But, for all these (fairly consistent) problems, the show has managed to produce some startlingly brilliant examples of horror since its resurrection, many of which are truly surprising in terms of what they contain, given that much of the target audience for the show consist of children and adolescents. Among the most notable examples of this are the truly superlative episodes The Impossible Planet and The Satan Pit. Occuring mid-way through David Tennant's first season, the episodes stand as a giant love letter to myriad forms of horror cinema, their sound-design, lighting, pacing and direction referencing far too many examples of film and even video game to catalogue, though there is a notable influence from the video game Doom in terms of concept, imagery and even certain sound effects lifted directly from the game itself. The set up is standard for any Doctor Who episode: the Doctor and his companion (in this instance, David Tennant and Billy Piper's Rose Tyler respectively) materialise randomly in a far flung space base; a grungy, extremely Alien-esque structure of cramped corridors, clanking, steaming pipes, rattling ventilation etc. Dread starts to curdle early, as they happen across a central chamber, writing scrawled across one wall that neither the Doctor nor Rose can read (an extremely sinister concept, as the Doctor's ship, the TARDIS, automatically translates all spoken and written languages). As the Doctor himself opines, this makes the writing impossibly old. That the Doctor himself is flummoxed (and more than a little unsettled) becomes a theme for the entire story, which continually throws impossibilities into his path and rarely stoops to explaining them. The situation grows more uncertain with the introduction of the Cthulhu-esque “Ood,” a species of tentacle-faced aliens that ostensibly seem to be a psychically-linked slave-race to humanity, almost mindless and lacking in all but the most subserviant impulses. Then there's the base itself, situated -as explained by its human occupants- on a planet that cannot exist, suspended by unknown means on the brink of a black hole, but never breaking orbit, never being consumed by the phenomena. The tension of the episode is masterfully increased by increments, situation layered atop situation, threat upon threat, until the true horror makes itself known: Something formless, faceless, but that whispers to the base's crew, inducing horrific visions in the weakest of them, eventually possessing him, resulting in one of the most brilliantly horrifying scenes in the show's entire run. Whilst the horrific set pieces are superbly well realised, what makes the story so atmospheric and engaging is the concepts at play; a formless, invisible entity, more of an elemental force than something defined, which even the Doctor can't describe or even, as it transpires, accept, when he comes face to face with it. This is the point at which Doctor Who shifts from science fiction into other realms; where it plays with metaphor and abstraction and opens up its own universe to eldritch and horrifying unknowns.  Of course, being the show that it is, it has little choice but to put some semblance of face and form to the entity, which, from an adult perspective, certainly dilutes the horror of it, but even after the revelation of the entity's physical form, the Doctor's inability to comprehend it, the creature's near-omniscient influence, still renders it a threatening and unsettling phenomena, even within a universe so infested with potential dangers. Interestingly, this is one of the rare instances in which the “monster” in question (hardly a suitable term, in this instance) isn't diluted by recurrences and over-familiarity; what is refered to most commonly as “The Beast” (yes, as in: Satan, Lucifer; the Devil himself, but, as the entity proclaims, not merely the Devil from Abrahamic mythology, but from ALL mythologies; an abstract creature that is the source and manifestation of all evil and negativity in the universe. Pretty hard to top that in terms of threat) never occurs again, though it is referenced passingly (there's less a story and more a potential suite of them waiting to be explored here). In stark contrast, the likes of the Daleks and Cybermen have, sadly, been diluted enormously by their consistent appearance and defeat: it's very difficult to continually promote a creature as threatening; the “...ultimate in genocide,” when they are consistently foiled by one guy and his entourage in a flying blue box. This is the problem with iconic enemies such as the Daleks, which have become so commonplace now as to have lost any semblance of the threat they exercised in previous seasons. They've even appeared in latter seasons as simply incidental, “cannon-fodder” threats that are simply the de rigeur “monster” in any Doctor Who episode when one is required to advance the story. An enormous shame, considering that there's certainly still potential in the core concept of both Daleks and Cybermen (for my money, they are at their most distressing when details are provided as to their natures and life-cycles; there's certainly an element of body horror to both species, since they are essentially surgically mutilated and/or genetically modified entities grafted into mechanical shells). The episodes that take time to explore the inner-workings of these creatures tend to exercise some of the most iconic imagery, especially since it provides a little insight into the true monstrosity that informs their natures (any episode which features a glimpse of the seeping, flailing, malformed thing at the heart of a Dalek, for example, lends the creatures a certain sense of dread and disturbance that they don't otherwise exercise when pristine in their outer shells. Similarly, episodes in which we catch glimpses of the butchered humanity at the heart of the Cybermen helps to enhance their horror). Certainly one of the most iconic entities to arise from the show in recent years are the “Weeping Angels,” entities that first occurred in one of the strongest episodes in the entire run: Blink. Manifesting as stone statues of seemingly crying angelic figures, the entities (like most of the horror-themed monstrosities in the show) are built around a central conceit that they can't move if someone is looking directly at them; in the sight of any creature, they “quantumn lock” (a form of self defence) and turn to unliving stone. However, they are so fast and vicious that even a blink is enough for them to stir and pounce on their prey.  The episode in which they initially occur is notable in that it hardly features the Doctor at all, save in the form of pre-recorded videos inserted into certain DVD tracks that seem to describe the phenomena of the angels but from the perspective of one having a conversation (as such, half of that conversation is missing, which renders the not-quite-dialogue quite chilling at times). A rare instance of an episode that focuses on entirely human characters, but that succeeds massively, it is (arguably) one of the most successful horror-themed episodes in the entire run, in that it builds with notable patience, never revealing too much to the audience or diluting its tension through over-exposure. The “angels” themselves are never seen moving; only in flashed moments of stillness, in which they shift from one posture to another in the space of a blink (another factor which lends to their already fairly creepy aesthetic). Just like the “Beast” before them, these entities are leant more gravitas by the manner in which the Doctor responds to them; though they are known to him, they are also genuine threats to both himself and the Timelords in general, older, even, than that most ancient of species, passingly described as “...creatures of the abstract, that feed off of potential energy.” In other words, they are metaphysical; most unlike the vast majority of enemies the Doctor faces that, no matter how absurd or bizarre, generally tend to operate within spheres of scientific possibility (or at least the patina thereof). The “Angels,” by contrast, are horrific not only in terms of their appearance and actions, but their description and mythology; they represent a bursting apart of the Doctor Who universe, in that they are creatures that operate outside of standard notions of possibility or physical law. In their original appearance, they are beautifully framed, rendered even more threatening by their scarcity; they rarely appear in full shot, and even then not for very long, leant an illusion of motion and speed by the movement of the camera itself. They are also one of the few Doctor Who monsters that are genuinely threatening from the off; the moment it becomes apparent what they are and what they do, they become terrifying, and beautifully so. They even have a bizarrely passive yet simultaneously chilling manner of dispatch (a concept that could have been played with far more elaborately than it, sadly, ever has been): rather than simply murdering their prey, they transport them back in time to an unspecified location and “feed” off of the potential energy of the days they will never live, whilst the victim ages and dies normally in a time-zone outside of their own. Unfortunately, as with the Daleks, degrees of over-exposure have diminished the angels quite significantly; they next appear in a two part story in the Matt Smith era, in which there is initially assumed to be a single specimen -threatening enough in itself-, but which is later revealed to be only one of an entire swarm (Choir?) in a state of hibernation, awaiting their opportunity to awake. Whilst this two-parter certainly has some stand out moments (a sequence in which companion Amy Pond is trapped in an enclosed space not with an angel, but with the flickering, projected image of an angel, that is purportedly just as deadly as the actual entity, is extremely fraught and beautifully directed, as is the conceit of the angel somehow entering her mind, making her count down throughout the episode towards...well, that would be telling, wouldn't it?). The problems regarding the angels and horror in Doctor Who in general are not specific to these episodes as such, but rather to the propensity of the show to overplay what proves to be successful: creatures such as the angels are terrifying and threatening because of their initial rarity; they are entities the like of which we rarely see in a Doctor Who episode (whose monstrosities tend to be of a more science fiction or technological bent), but which become less and less threatening the more they occur. When we finally reach the conclusion of Amy Pond's run as the Doctor's companion in the episode Angels in Manhattan, the entities have effectively become parodies of themselves; a trajectory that echoes those of recurring villains such as the Daleks and Cybermen. The Weeping Angels encapsulate all that is fantastic and abysmal about horror in Doctor Who: an enduring, culturally resonant image characterised by a witty and effective in-built conceit (“Don't blink. Not even for a second. Blink and you're dead.”), framed and shot and designed beautifully, but fundamentally limited by the same strengths: once the central concept becomes familiar, it is immediately in danger of being over-played, which sadly renders all subsequent appearances of the angels more and more diluted, to the point whereby they become just another background monster. This serves as a superb example of how horror generally works in Doctor Who: most of the creatures that occur in the overtly horrific episodes tend to be high concept; they have a particular idiosyncrasy, tick or characteristic that makes them identifiable and culturally resonant, from the “Are you my Mommy?” gas-masked child of The Empty Child to the ticking, whirring clock-work men from The Girl in the Fireplace, the use of particular sounds, repeated phrases, strange physical ticks and tremors, all serve to lend the menagerie of monsters and entities Doctor Who provides certain degrees of identification, but also a Pavlovian sense of dread that, in the hands of good writers and directors, can be used to pre-empt and manipulate audience reaction, cued at just the right moment to elicit dread, shock or repulsion. Another superb example derives from the latter stages of the Matt Smith era in the form of “The Silence,” entities that resemble the classic, “Area-51” greyling alien of pop-culture myth (evoking a certain culturally ingrained response through design alone), but also exhibiting a central concept that lends them not only a superb element of dread but also in-built narrative tension: they can only be observed when they are looked at directly; the instant someone turns away or they shift out of view, the observer instantly forgets that they even exist, rendering them bizarrely invisible. This allows for some truly fraught and beautifully executed set-pieces, in which characters have to rely on markings and warnings scrawled on their own skin in order to remember what they are fighting. Again, a conceit that works beautifully in the first episode or so in which it occurs, but which loses bite and significance with every repetition. Another issue concerning the Silence, but which also has wider ramification for the series as a whole, is that the format of conceptualising monsters and antagonists around very specific central concepts is that the concept itself has the quality of distracting from or drowning out actual story; there is a marked tendency for monsters such as the Silence to occur in stories that are under-baked or lacking in certain key areas, because far too much emphasis is placed on the concept rather than the wider mythology, framing and plot. This often has the effect of iconic creatures dwindling to common or garden Doctor Who dross following their initial exposure, as, outside of the core concept, they have no wider relevance or potential; nowhere to go in terms of wider story. This is certainly the case for the Silence, who feature fleetingly a few times more before being wrapped up entirely at the conclusion of the Matt Smith era.  By contrast, there are numerous examples of singular episodes that feature creatures, situations and concepts that have never been returned to or repeated, and which therefore retain their power to terrify. Amongst them stands what is arguably the most effective “horror” episode in the entire canon: the superlative Midnight, which is not only a fantastic Doctor Who episode, but a rare and brilliant example of how to orchestrate horror in a limited space with a rarefied cast of characters and, fundamentally, no monster; no big special effects, no grand reveals or explanations, which renders the entire episode chilling by contrast alone. The episode begins unusually, in that it isolates the Doctor; separating him from both his TARDIS and his companion (in this instance, Catherine Tate's superb Donna Noble), not by throwing him into some contrived calamity, but innoccuously; the Doctor embarking on a kind of group safari across the uninhabitable diamond wastes of the eponymous planet, whilst Donna elects to stay behind in a luxury resort. Almost the entire episode is filmed within the confines of the armoured carrier that escorts the guests out across the wastes and protects them from the planet's lethal radiation. The early scenes are extremely casual and banal, though entertaining; the Doctor taking time to speak with each of his fellow passengers, allowing the audience to engage and identify with them, which, of course, makes events that follow all the more horrific: Inevitably, the carrier breaks down whilst taking a slight detour through the wastes, owing to apparent avalanches of the surrounding crystal glaciers. Whilst speaking with the pilot of the carrier, a moment of subtle dread is introduced: as the shutters come down to protect the crew from the lethal radiation, the pilot claims to have glimpsed a figure in the distance, running towards the carrier. The audience is shown nothing. This is the kind of horror that Doctor Who can potentially do so well; making a virtue of its lack of budget in the same manner as independent horror films; drip feeding and suggesting what might be happening rather than making matters overt in the forms of big, latex, rubber and CG monsters which, whilst part and parcel of the show's ethos, are also often in danger of becoming formulaic and over played (at its worst moments, the show effectively becomes “situation and monster of the week” with very little to distinguish between one episode and the next). Returning to the primary cabin, the Doctor finds a situation of escalating tension, as people start to panic, as theories run wild, as people feed on one another's fear in an extremely tense and claustrophobic environment. A central part of the horror in this episodes derives not from any external threat, but of what humans will do and exhibit when in fear for their own survival. The situation starts to degrade as something starts to bang on the carrier's hull, seeming to answer when the Doctor knocks back. The phenomena is rendered even more threatening by the absolute conviction of those on board that nothing, nothing can possibly be alive on Midnight's surface, rendering the potential entity beyond the remit of reason or science.  Following the build up of tension, the situation explodes into chaos as the carrier rocks back and forth on its wheels, systems spark and sputter, lights dim and the cabin area, housing the pilot and co-pilot, is torn away, leaving the passengers stranded, awaiting rescue by a previously contacted team. It's at this point the episode ramps up the horror, not showing any invading or hostile entity, instead focussing on a particular passenger who begins repeating everything that the others say, glaring at them each in turn in a distressing, reptilian manner. The episode lives or dies at this point by its framing, direction and performances, and all are superb. Absolutely superb; the episode is highly experimental, inverting many of the standard traditions of Doctor Who in general, providing no abstruse, science fiction explanations, no overt monster, rendering the Doctor almost powerless by the episodes end, as the entity inhabiting the character Skye Sylvestri begins to not only repeat his words, but to pre-empt them, effectively stealing his voice and rendering him catatonic, playing on the fear and paranoia of the other passengers, urging them to hurl him out of the carrier, into Midnight's lethal wastes. By placing the Doctor in ignorance and jeopardy, the episode unsettles the audience to such a point that they feel almost afraid to watch, that they operate in states of tension and paranoia that echo those of the characters themselves. That the Doctor is almost murdered by this unknown, unseen entity; that the human characters he was happily interacting with barely an hour before are so willing to sacrifice him, renders the episode not only terrifying, but also fairly misanthropic; a far from flattering commentary on the state of humanity at its most desperate.  Another factor the show utilises to induce fear and paranoia in its audience is by inverting the tropes of Midnight, as in the episode Blink, which introduces the Weeping Angels, and the fantastic Turn Left, in which it removes the Doctor himself, leaving responsibility for solving the various crises that occur to the companion and supporting characters. This has the effect of unanchoring the show; whilst the Doctor is present, there is always a solution; a potential “get out” clause. Removing him removes that narrative safety net, leaving both characters and audience adrift. Turn Left is perhaps the most remarkable example of this, in that it presents a “what if?” scenario in which time and destiny are synthetically altered so that Catherine Tate's Donna Noble never met the Doctor, meaning that he died long, long before current events, and wasn't present to insulate the earth and the wider universe from a series of calamities that ultimately brings humanity to the point of extinction, the universe to unravelling. The horror presented in Turn Left is of a very, very different flavour to that present in almost the entirety of Doctor Who; not deriving from any immediate or specificied threat, it rather relies on audience knowledge of what should be, whilst protagonist Donna Noble remains blithely ignorant of her significance. There is no specific “monster of the week,” here, save for the entity by which time is synthetically altered, no immediate threat or situation; rather, the episode serves as an overview of past events, providing alternative outcomes had the Doctor not been present to solve them. As such, the state of planet Earth quickly degenerates, as catastrophe upon catastrophe, invasion upon invasion, slowly reduces the planet to an immense warzone. Throughout this chaos, Donna Noble wanders with a vague but unspecified sense of how wrong it all is, that things should be different, but not knowing how or why until the re-emergence of long-absent companion and fan favourite, Rose Tyler, who provides the means by which she might set time back on its correct course, but also makes clear the sacrifice that is required. The episode exercises a kind of dull inevitability; a dread of an entirely more expansive, slow-burning kind, that grows and grows as the state of the Earth degenerates, as atrocity after atrocity accumulates, resulting in a final calamity whose cause isn't determined in the series until its closing episodes, in which the stars begin to blink out one by one, leaving the night sky empty... a chillingly brilliant image, that crowns a series of hopeless and hideous moments, the episode rare and unusual amongst the canon of Who in so many ways, not least of which for almost entirely excising the Doctor and allowing the companion to take centre stage (a gamble which so often does not pay off, but here provides one of the strongest episodes that has ever aired). More recently, the show has demonstrated a penchant for abstruse -but not always successful- experimentation, playing with established literary tropes and ideas deriving from a wide variety of genres, attempting to lampoon them in such a manner as to distinguish itself through its writing and storytelling, rather than the relative intrigue of whatever monster it happens to feature. A fantastic example is the Peter Capaldi episode Listen, which features no monsters or entities that the audience is privy to; only the suggestion and possibility thereof, focus instead shifting to a hypothesis on the Doctor's behalf; that there are unseen entities that have evolved such a perfect camouflage, that they are never observed, only ever felt in a vague and unsettling manner, that are always present, but have never been identified; that lurk in secret places such as in closets and under the bed. The episode is notable in that it plays with established horror techniques, tropes and set-pieces, but cleverly lampoons them by providing no specific pay-off; always dragging the audience away from the action when it seems some conclusion is going to be reached. The relative success of the episode relies upon how willing the audience are to put aside preconceptions of what Who is and how the show functions; it is highly unusual, in that there are no action set-pieces; no moments of high energy, only a slow burn of escalating dread, as the Doctor seeks almost obsessively for evidence of an entity that may or may not exist, culminating in a moment at the very end of all time, when there is nothing beyond the walls of the vessel in which he and companion Clara Oswald find themselves, at least, nothing that can be readily conceived... Likewise, the high concept episode Sleep No More features a variety of novel techniques and concepts in Who, not least of which being that the episode is shot almost entirely in the first person, from the perspective of what appear to be helmet and wall mounted cameras, but which are later revealed to be something entirely other. The episode thereby references the classic tropes of documentary horror, in that the format becomes part of the mythology; the “camera” itself a conscious entity and agent within the story. The episode maintains a certain status (stigma?) in the Doctor Who fandom, in that its conclusion polarises to extreme degrees: some regard it as a work of subtke genius, others of ill-written vagary. Either way, the episode maintains a certain fascination, in that it can be returned to again and again, new subtleties and details becoming apparent with every viewing.  Arguably the zenith of high concept Who, the episode Heaven Sent demonstrates yet another facet of how the tropes of genres can overlap or be subjected to certain confluences within the show; simultaneously a work of subtly brilliant horror and intelligent science fiction, the episode wraps up certain story elements that litter the preceding series, as well as providing some fascinating insight into the Doctor himself. Following companion Clara Oswald's death in the previous episode, the Doctor is teleported against his will to what appears to be an ancient castle that is, despite its decrepitude, equipped with a variety of advanced equipment (not least of which being the teleporter that transported him there). Exploring the castle, he finds a variety of bizarre clues as to what has transpired there to render it so utterly abandoned (a pile of ash on the floor, in which is scrawled the word “bird,” a pile of wet and discarded clothes that match his own, a variety of sealed doors, rooms and corridors that lead nowhere). Pursued by a shambling, fly-blown figure -always heralded by a carrion buzzing-, he comes to the conclusion that the castle is some form of personal torture chamber, designed by an unseen enemy to harass and torment him. Whilst in flight from the shambling, undead figure, he recounts a memory from childhood, in which he saw one of his fellow Timelords dead for the first time; an image that the spectre seems specifically derived from, to terrify him into revealing secrets and betraying conspiracies that are the only means of escaping it (the figure always pauses if the Doctor recounts something true and deeply personal; something he has kept hidden from the universe all his long life). Likewise, the castle itself shifts and twists around him, altering its structure to allow him access to different areas at varying points in its cycle. He soon discovers that there is no escape; the castle has no means of exit, surrounded on all sides by an ocean whose depths are littered with the skulls of previous incumbents, his TARDIS sealed behind an immense wall of diamond-hard matter. The entire episode is structured as a simultaneous dark fairy tale and metaphysical mystery; close focus is paid to the Doctor in the aftermath of Clara Oswald's death, the episode featuring no other characters, no one and nothing for him to play off but himself and his own haunted memories (of which the castle seems to be some sort of expression). The quiescence, the strange silence; the depths that the Doctor reveals through his confessions...all conspire with the threat provided by the creature that stalks him to instill a sense of profound and waxing dread; one that, unlike in most Doctor Who episodes, culminates with not only the Doctor's defeat, but his death. Many, many times over, each time resulting in a new resurrection from the teleporter that initially brought him there, time moving forward incremently through billions upon billions of years as he slowly chips away at the diamond hard matter sealing him away from his TARDIS, until, finally, one of his latter incarnations breaks through...  It's an episode and, indeed, a story that is troubling on a number of levels; it reveals the Doctor in a very unflattering light; as a dogged, self-despairing, self-destructive entity, who is willing to go through Hell a billion times over out of his own tenacity and sense of vengeance. That, alongside the true horror of its science fiction elements (bringing into question common subjects such as teleportation, time travel, reincarnation and so on and so forth) makes for what is arguably one of the most successful episodes ever written, the horror of which is slow-building, complex and deeply layered, blackly rich and compelling. This is where Doctor Who shines not only in terms of its potential for horror, but for simply playing with ideas. At its very best, the show operates as kind of playground or theatre in which abstruse or unusual subjects and forms of storytelling can be played with, not to mention introduced to audiences that might otherwise not be exposed to them. That the show is marketed as a family product; suitable for all ages, regardless of its content, renders its occassional successes in experimental horror, science fiction et al all the more appealing, as it provides younger audiences access to subjects, forms and materials they may not otherwise have opportunity to experience (certainly not until much later). The restrictions imposed by its intended audience may, conceivably, act as a parameter to certain forms of horror (you will rarely find anything approaching extreme gore or bodily mutilation in Doctor Who, though it does play with those subjects on occasion), but also force a certain degree of invention when it comes to its presentation; much of its threat and overt horror elements are implied rather than explicit, which renders them all the more engaging and immediate, as the audience is forced to fill in the blanks with their own imaginations. At its worst, horror in Doctor Who is overblown, formulaic and utterly risible; the apparent “threat” introduced has no bite or weight (largely owing to over-exposure, as in the cases of the Daleks, Cybermen etc) or is framed in such a manner that it appears more comedic than dreadful. Others are merely misconceived; the central premise simply doesn't work or is underbaked, which is sadly inevitable on a show with so many writers bringing their own styles, preconceptions and imaginings to the table.

But when it gets it right, it is cause for sincere celebration, as it not only trespasses beyond its own parameters as a show, but also pushes those of the myriad genres it features. |

AuthorGeorge Lea is an entity that seems to simultaneously exist and not exist at various points and states in time and reality, mostly where there are vast quantities of cake to be had. He has a lot of books. And a cat named Rufus. What she makes of all this is anyone's guess. Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed